How West Indies attained Test match status

Giles Wilcock takes us down memory lane once again with a look at the birth of West Indies as a test 'nation'

In 1928, West Indies became the fourth Test playing team after Australia, England and South Africa. But this was not their first experience of international cricket. The 1928 tour was the fourth time a West Indies team had visited England. Over forty years after playing their first matches, the final promotion of the West Indies to Test status was effectively the result of one hour's astonishing cricket in the unlikely venue of Scarborough in 1923.

The idea of a "West Indies" team dated back to 1886 when an all-white side toured Canada and the United States. At the time, regional sides deliberately excluded black players, so the first West Indies teams were comprised solely of white cricketers. The West Indies began to play more frequently as growing numbers of English teams of varying ability began to organise tours of the Caribbean that were partly sporting events, but mainly social occasions for upper-class Englishmen. If the cricket was hardly of the highest standard, it cemented the idea of the best players in the region coming together in one team, the West Indies team.

The idea progressed further when the West Indies visited England for the first time in 1900. The team played several leading counties which represented a huge challenge and a considerable step up in the standard of opposition. The tour was viewed as an interesting experiment, but not taken too seriously by the English, who did not award the games first-class status. From the West Indies' point of view, results were respectable and several men performed well — not least the four black players included as a necessity to make the team competitive against strong opposition.

There was enough interest for the West Indies to tour England again in 1906, and this time the matches were given first-class status. Now that a precedent had been set, more black players were selected. However, several English journalists commented negatively on the idea of a team containing both white and black players, scoffing at the idea of Australia or South Africa fielding similarly mixed elevens, and results on the field were poor.

In fact, England suddenly lost interest in West Indian cricket. Around this time, the English authorities began a concerted effort to cultivate closer cricketing ties between England, Australia and South Africa, culminating in the ill-fated "Triangular Tournament" of 1912. One of the leading figures in this movement was the South African Abe Bailey, who wished to keep cricket in the hands of white English speakers. Bailey had strong ideas on race: the Australian cricket historian Gideon Haigh describes him as "the basest of racists". Perhaps it was a coincidence that after 1906, West Indian cricket was relegated in this grand imperial project.

But perhaps not.

No West Indian team toured England for seventeen years, although a couple of weak MCC teams toured the Caribbean shortly before the First World War. During the intervening years, West Indies cricket had continued to involve both white and black players, although all the captains, selectors and administrators were white.

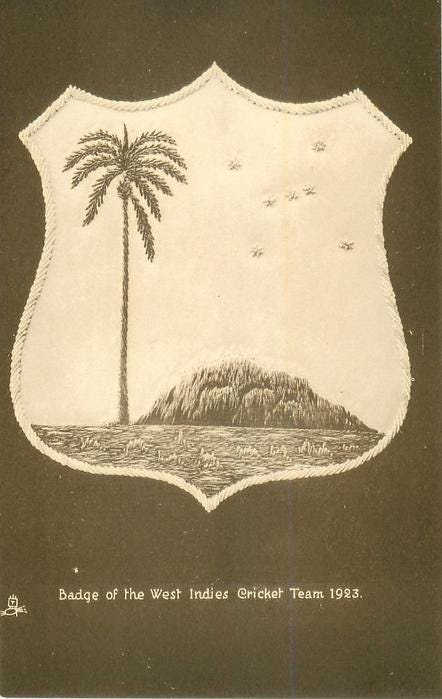

The West Indies were finally invited to tour England again for the 1923 season. Having been isolated for so long, there were few external yardsticks against which to judge the players. To complicate selection further, it was agreed that each of the main colonies — Barbados, Trinidad, British Guiana and Jamaica — would be allocated a certain number of places in the team. This meant that some good cricketers were omitted. Around half of the sixteen players were black; it is likely that white players were favoured in borderline cases, but the team was a strong one based on home performances.

After a slow start — caused in part by the unaccustomed English weather and the unfamiliarity of playing up to six days a week — the team recorded some good results. Of 20 first-class games, they won six and lost seven, which was more than respectable, particularly as they improved as the tour progressed. They were captained by the 46-year-old Harold Austin, who first played for the West Indies in 1897 and had toured England in 1906. Although missing some matches through illness, he had a reasonable batting record and captained the team effectively.

But the batting star of the tour was the white Barbadian George Challenor who impressed with his stylish play, scoring six first-class centuries and averaging over fifty. His record compared favourably with the leading English batsman of the period, and he was judged to be among the world's best batsmen. The rest of the batting was somewhat uneven, and there were several failures. Other than Challenor, only Maurice Fernandes of British Guiana and Trinidad's Joe Small averaged over thirty in first-class games.

Joe Small first man to score a test 50 for the West Indies

But the batting of the team was not what commanded attention. Nor was its fielding, although the young Learie Constantine stood out as exceptional. The support bowling was respectable without having too much impact. Small filled in some overs with his medium pace, while Victor Pascall, Constantine's uncle, was steady. So too was "Snuffy" Browne of British Guiana, who bowled more overs than anyone. None of these three were especially penetrative, particularly against the best batsmen.

One thing set the team apart, making critics sit up and take notice. The West Indian fast bowlers stood out as exceptional. George John of Trinidad, nearing his 40th birthday, was past his best, but was still capable of occasionally terrorising batsmen. He was a remarkable character, and not a man to be crossed on the cricket field. John's record in 1923 — 49 wickets at 19.51 — was very good. But it was his opening partner who made waves. George Francis of Barbados took 82 wickets at an average of 15.58. The key to his success was his preferred tactic — out of fashion at the time — to bowl directly at the stumps. He took ten wickets in a highly-creditable victory over a strong Surrey team, and his record was far better than any other fast bowler in England that season — in fact, there were hardly any other men of his pace playing county cricket at the time.

Looking at the results of the tour, other than the performances of Challenor and Francis, little stood out as exceptional. Yet, just three years later, the West Indies were awarded Test status. What was it that made such an impression on English crowds and critics?

The answer lies in the last match, part of the annual end-of-season Scarborough Festival. Each year, teams of leading players played what were sometimes little more than glorified exhibition matches by the sea, but some interesting and entertaining cricket took place. One of the leading figures in the festival was HDG Leveson-Gower, a former Surrey and England captain, who often selected a team to play matches against touring sides. So, at the start of September, the West Indies faced "HDG Leveson-Gower's XI" containing ten current or future Test players plus the fifty-year-old Leveson-Gower, who had played for England in 1910; it was not far short of what would have been the full England Test team at the time — quite a compliment to the West Indies.

The first two days were unremarkable. The West Indies were bowled out for 110 by an attack which contained three men who had bowled for England in the 1921 Ashes series and a fourth who would play in the 1926 Ashes. Although John and Francis took four wickets each, Ernest Tyldesley scored 97 to set up a first innings lead for Leveson-Gower's team of 108. But, in a sign of what was to come, the legendary Jack Hobbs and the future England captain Percy Chapman were the only other men to reach double figures as the last five wickets fell for 16 runs on the second morning. But the West Indies could only score 135 in their second innings.

When Leveson-Gower's team batted a second time in front of a few hundred spectators early on the third and final day of the game, they needed just 28 to win on a pitch that continued to play well. The next 70 minutes changed the course of West Indies cricket history. From the start, it was clear that the West Indies had not given up. In the second over of the innings, bowled by Francis, Jack Hobbs hit the third ball in the air to long leg where Austin put down a difficult one-handed chance. But that was just the start of an incredible session of play.

In the fourth over, with the score on 3, Hobbs was lbw to Francis, playing across a straight ball. A cagey few overs followed before the other opening batsman, Greville Stevens, was caught low down at backward short-leg by John off the bowling of Francis. Six runs were eked out from the next four overs by batsmen palpably struggling. John was bowling faster than he had earlier on the tour — noticeably faster than Francis, and from the fourth ball of the thirteenth over, he had Tyldesley, the first innings hero, caught in the slips by Snuffy Browne. The score had crawled to 14 for three, and the new batsman Wilfred Rhodes survived a confident shout for lbw in that same over. He scrambled a leg-bye to keep the strike but looked out of his depth. Facing Francis, he survived another lbw shout before he edged a catch to the wicketkeeper. Rhodes was out for a duck with the score 15 for four. Having hit his first ball confidently through the covers for two, the new batsman Chapman was yorked by John, facing his second ball, in the next over.

The score now was 17 for five, and there was enormous tension at the ground. The former England captain Johnny Douglas, who had seen three wickets fall, continued to block at one end, and two more runs were added to the score, one to him and one to Frank Mann, the new batsman. As Mann prepared to face Francis, Austin took his time to arrange the field carefully, taking out short leg, putting mid-on back and placing John at silly-mid-on. From Francis' first ball, Mann was caught by John in the very position set up for him. The score was 19 for six and Leveson-Gower's team still needed nine to win. As the report in the Cricketer magazine said a few weeks later, "so deadly was the bowling that when the sixth wicket fell … one was prepared for anything."

The new batsman was Percy Fender, Surrey's captain, and not one to hang around. He managed to keep out a first-ball yorker from Francis, was beaten outside off-stump by a ball which just missed his wicket and then took a single. In the next over, bowled by John, he survived another lbw appeal, but took a two and a single. Bowling to Douglas, John then delivered a no-ball. As the no-ball rule at the time concerned the positioning of the back foot, rather than the modern front-foot regulation, Douglas had time to hear the call and adjust his shot (a similar effect to a modern "free hit"); he took a huge swing at John and edged the ball over the slips for four to level the scores. The end came next over; from the fourth ball, Fender edged Francis for four between the wicket-keeper and first slip to give Leveson-Gower's team the luckiest of four-wicket wins.

Over two days, John and Francis had taken eleven wickets for 51 runs between them while playing a side which was widely acknowledged as a very strong one. The crowd cheered the players off the field, and Austin's captaincy was praised. Reports also noted that the bowlers were unlucky on that third morning; even at the time it was recognised as a potential turning point for West Indies cricket. English critics, while worrying how much panic had been spread among the cream of English batting by the effects of pace bowling, acknowledged the brilliance of the West Indian performance at Scarborough. The match was talked about for many years, both in England and in the Caribbean.

From this point, everyone began to take West Indies cricket seriously. When an MCC team toured the region in early 1926, it was far stronger than previous visiting sides. The MCC played three unofficial "Tests" against a West Indies team, winning the only game to be completed — but a report in Wisden recorded: "Well-equipped as [the MCC] were in all respects, the team met with such powerful opposition on almost every occasion that the tour afforded further evidence of the rapid progress of the game in the West Indies."

Later that year, at a meeting of the ICC (then officially called the Imperial Cricket Conference), the West Indies were given full Test status and a tour of England was arranged for 1928. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons which included poor selection and abject mis-management, that tour was an utter failure. It would be another twenty years before the West Indies were as competitive as they had been at Scarborough in 1923.

Giles Wilcock

As ever if you would like to have content published on the newsletter by all means feel free to drop us an email.

Leave a comment below or reply via email with your response to Giles’ article. Your interaction is what helps grow the community and we appreciate every response.

Also keep an eye out for our next podcast episode next week (on all podcast platforms), a fantastic interview with CWI Coach Education Manager Chris Brabazon.

CR (Snuffy) Browne and Berkley Gaskin were the " first" coaches of a Combined High School team in Guyana that I was a part of

CR Browne was Barbadian not Guyanese, he ended up living and playing cricket for Guyana then British Guiana for years