After a quiet sporting period of seven years with barely any high-level cricket being played, Caribbean society was in a state of flux.

By the end of the 1930s, labour revolts throughout the region became increasingly widespread. The centralisation of the plantation economy, which had plagued its society since its inception, created enormous unemployment in places like Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, prompting a large migration from traditionally rural communities into the major urban centres in search of jobs.

Working conditions had not improved in the slightest. With the price of sugar plummeting, workers in Saint Kitts demanded better wages and working rights, leading to a strike that resulted in three fatalities. In Trinidad, a number of workers’ organisations had begun to emerge, particularly within the oil industry, such as the Negro Welfare and Cultural Association, which organised hunger marches. During the same period, the United States stopped accepting West Indian migrants, causing a huge population influx back into the islands—largely unemployed and without infrastructure or support.

The Royal Commission Report of 1938 summarised the situation in Jamaica and the dire living conditions faced by many returning migrants: ‘At Orange Bay the commissioner saw people living in huts, the walls of which were bamboo, knitted together as closely as human hands were capable; the ceilings were made from dry chipped coconut branches which shifted their positions with every wind.’

Heading into the post-war period, the Nazi bombings of Britain had caused vast destruction to local infrastructure and industry. The solution was to bring in migrant workers to aid in reconstruction. At the same time, in 1944, a hurricane struck Jamaica, devastating large portions of the banana and coconut plantations. Thousands lost their homes due to the natural disaster, and thousands more were displaced due to unemployment. For many of these individuals, the logical option was to seek work in the British Isles—sometimes temporarily, sometimes indefinitely.

Known as the Windrush period, the number of Caribbean people in Britain rose from around 8,000 in 1931 to over 170,000 in 1961. A new West Indian presence was established in England, reshaping not only society but also language and culture forever. A tremendous influence in this period was the Caribbean Labour Congress (CLC), established in 1945 to provide a more effective platform for Caribbean political figures and union leaders. It grew into an inter-island organisation focusing on an independent West Indian federation and self-reliance.

Their influence spread to England when they opened a branch in 1948, supporting federation and fostering a strong nationalist, anti-colonial mentality. At the time, they were the driving force behind West Indian nationalism in Britain. George Padmore himself stated at one meeting, ‘Federation is the immediate objective.’ As the author Eleanor Kramer-Taylor claims in her article Forging the West Indian Nation, the London branch was ‘for its contemporaries, a beacon of Caribbean nationalism in Britain.’

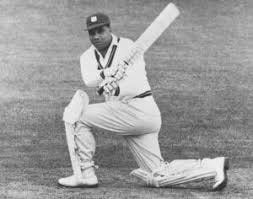

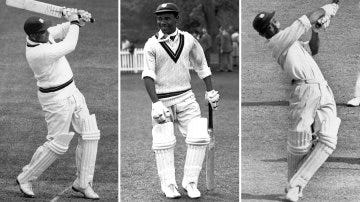

While all these events were shaping and influencing society at large, in February 1946 at Port of Spain, two Bajans set the record for the highest West Indian partnership in any format—574 runs for the fourth wicket. These two individuals would fundamentally change cricket in the Caribbean: Clyde Walcott, a tall man, over six feet in height with a strong physique, also served as a wicketkeeper, scoring 314 not out. His partner, Frank Worrell—the future captain of the team—was tall and lean, batted right-handed but bowled left-arm slow. He was a class apart, and Wisden described him in remarkable terms: ‘For beauty of stroke, no one in the history of the game can have excelled Worrell.’ A missing name from that innings was Everton Weekes—shorter and more compact than the other two, quick on his feet and a natural cutter of the ball. Having played a match in January 1945 after returning from war duties, he joined Walcott and Worrell for the first time in a match for Barbados in Trinidad.

In 1948, nearly ten years after the last Test played by the West Indies, they embarked on their first post-war tour. In stark contrast, England had already played four series by this point. Arguments could have been made that this was not a full-strength English side, but the sheer difference in match experience between the two teams rendered those arguments meaningless. Yet in 11 first-class matches and four Tests, England were completely outplayed and embarrassed, failing to win a single match. Gubby Allen, the English captain, had an embarrassing campaign—at 45 years old, he was nowhere near fit for any of the matches, even pulling a calf muscle while descending the boat. Wisden paints a remarkably pathetic image of the team, unable to handle the heat or the constant travel between the islands. The only player who fared well was Jim Laker, arguably England’s finest off-spinner of all time, who took 18 wickets in seven innings.

It is in the first Test match of this tour where we see the first black captain of the West Indies, George Headley, at 38 years old and still playing for the team, now having the opportunity of captaining the side. In the first innings he only made 29 and pulled a muscle fielding when England was batting second. He would not take part in any of the other matches cutting his captaincy short.

In the first Test at Kensington Oval, two of the Ws would partake: Walcott behind the stumps and opening the batting, and Weekes batting at three. Worrell did not play in the first Test due to suffering from a case of food poisoning; it just wasn’t meant to be.

The stars of the match were Stollmeyer, who was still playing well even after the war, and Gerry Gomez, a batting all-rounder with a good and quick action. The two of them got the team to 244/3 on the first day. Laker, however, broke the partnership, and the other wickets fell quickly ending the first innings on 296.

The pace attack of Prior Jones, Foffie Williams, and Berkeley was able to get seven wickets and finished England’s knock for only 253. Still leading by 43, West Indies came out to bat again. Robert Christiani was the standout in the second innings. A fine, gritty, right-handed Guyanese batsman, he scored 99 yet as as good a knock as it was by Christiani, Foffie Williams was the one to break records that day. In his first six deliveries, he scored 28 runs, hitting Jim Laker for two sixes and then two fours in a row. He went on to score the fastest half-century by a West Indian at the time, in only 30 minutes, and ended up with 72 from 96 balls.

After scoring 351, the West Indies declared and gave England an impossible target of 394. It would not be a dramatic finish, with rain coming at four wickets down and the match ending in a draw.

The second match was also a draw, with rain on Sunday losing two hours of play and making the outfield sluggish. Stollmeyer was out with an injury. With Headley being ruled out of the tour, Gerry Gomez took the captaincy, and Frank Worrell, feeling better, came back into the side for the second Test in Trinidad. Again, there were no major scores from Walcott or Weekes, but Worrell, in his first international innings, went on to score a beautiful 97, delighting the crowd and journalists with his impeccable control and movement. Nothing else of note occurred, with the exception of Wilf Ferguson, a Trinidadian leg-spinner, who got his best innings figures of 6/92 and a match ten-wicket haul, with 11/229 in the match. The most humorous part of this spell was that whenever he took his hat off, the crowd would cheer loudly at the sight of his clean-shaven bald head.

The next two Tests were a showcase of West Indian domination. Frank Worrell scored an unbeaten 131* as the West Indies posted 297. England could only score 111 in reply and when the follow on was enforced they were only able to score 263 runs, leaving West Indies a comfortable chase and a seven wicket victory.

In the final Test at Sabina the three Ws came to the fore. The match’s star was Everton Weekes, scoring the highest score of the entire series with 141 runs, driving well and confidently with no sign of hurry. With 490 on the board, the standout bowling performance was from Hines Johnson, a Jamaican fast bowler, who got the best bowling figures for a West Indian on Test debut with 10/96.

The West Indies eventually won by 10 wickets sealing an unbeaten series.

Not long after England had left at the end of April, the men in maroon embarked on their first-ever tour of India in November of the same year until February of 1949. It was a full tour with five Test matches, all of them allocated five days for play, but even then, four were drawn, with only one victory for the West Indies side in the fourth Test at Chennai. The draws were not caused by bad weather as much as they were caused by a weak pace attack. With no Hines Johnson in the squad, the only standout performance was from Prior Jones, who got 17 wickets in ten innings, averaging 28 apiece; all other bowlers, with the exception of Gomez, averaged above 35.

As bad as the bowling was, the batting was utterly dominant. Allan Rae made his debut on the tour, a white, middle-class Jamaican opener, genuinely chosen for merit, unlike some of the previous white players who were of a solely upper-class background.

Rae had a brilliant season, averaging 53.43, with two centuries and a high score of 109, together with Stollmeyer in the 4th Test, they established a record first-wicket partnership of 239 for the West Indies. Headley was called in for the tour, but at his advanced age, he only played in the first Test, which would be his last international match.

Most importantly, this was the breakout tour for Clyde Walcott and Everton Weekes, the former scoring 152 in the first Test, taking part in the highest fourth-wicket partnership at the time with Gerry Gomez, with 267 runs scored between them. In the same innings, Weekes went on to score 128 runs in just over 3 hours.

While Walcott did brilliantly, averaging 64.57 and keeping during all matches, the brilliance of Weekes could not be undermined. He was the first batsman in history to score five centuries in consecutive innings, his first one came in the last Test against England, and the rest in the first three matches against India. He finished the tour averaging 111.29 without a single not out in 7 innings.

Weekes was quick on his feet and had some of the best wrist movement and positioning in world cricket; his technique was second best only to Worrell himself, which readers might find odd, as this article has yet to really mention Worrell.

The official reason for Worrell not being included in the tour to India was that he’d decided to stay in England due to league commitments in Lancashire; that, however, could not be further from the truth. The real reason was a wage disagreement between him and the board. He asked the board for £250 to tour India; considering that a disrespectful attitude, they denied him payment and, as punishment, excluded him from the tour. This was not the first time a conflict over a better wage had occurred between Worrell and the board, and it would eerily reflect the modern fights between the former WICB and players with T20 league contracts.

Gerry Gomez said that ‘Frank told me later that the shock of being excluded from the touring party was the best thing that could have happened to him,’. Worrell would go on to join the Commonwealth XI to tour India in 1949 and would cement his place as the best batsman of the time, no doubt.

In that tour for the Commonwealth, Worrell scored a staggering 1640 runs, averaging 74.54 by the end of the tour. On what he considered to be his best knock of the tour, at Kanpur on a matting wicket, he was able to score a fine 223 in six hours on an excruciatingly difficult pitch He took his time and patience, timing the ball to perfection. This would not be the last time Worrell went to India under the Commonwealth banner, but this first tour was the perfect demonstration of how important he was to the West Indies side.

Prior to the start of the pivotal England tour in 1950 the WICBC organised four inter-colonial matches, two between Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica in Port of Spain, and two in Barbados against British Guiana.

The standout bowlers were from the Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago squad, but in the Barbados game, Weekes scored 236* and 121, and Walcott with 211*, overwhelming Guyana completely.

The quality of these two aside, the key pair would be the spin duo of the Jamaican Sonny Ramadhin and the Trinidadian Alf Valentine. Ramadhin was a right-arm off-spinner who could bowl a wrong’un going away from the right-hander. There was no apparent change in his action, which baffled both domestic and international opponents. With figures of 5/39 and 3/67 in the first match, and 4/76 in the second one, he was a clear pick. Valentine, on the other hand, didn’t perform as well as Ramadhin. He bowled 39 overs without a single wicket, conceding 111 runs in the process.

That said being a left-arm slow bowler, his biggest advantage was being left-handed itself, with a good arm ball that impressed the selectors. Following the old wisdom that you have to bring a left-hander to England, he was included for the tour. This proved to be an inspired decision.

Thirty-one first class matches were scheduled and four Tests were played. With a newly developed and established top order, of Stollmeyer and Allan Rae opening ably supported by Worrell at three, Weekes at four, and Walcott at five the West Indies were expected to be a difficult proposition to contend with. Ramadhin and Valentine joined a pace attack of Hines, Johnson, and Prior-Jones.

In the third match of the tour against Surrey, against a good bowling attack of the off-spinner Jim Laker and the medium-pacer Alec Bedser, Weekes scored 232.

In the following match against Cambridge University, 1,324 runs were scored in just two innings for a total of seven wickets in three days of cricket. Walcott scored 160 and Weekes an unbeaten 304, totalling the highest first class score for a West Indies side in England at 730/3.

It was the last match before the first Test where we would see the brilliance of the bowling attack. Against Lancashire, Valentine was able to claim 13 wickets for 67 runs, a foreshadowing of what was to come for the first Test.

The first Test will always be remembered for a pitch controversy, where, by orders from the Lancashire Ground Committee, they used less water and the heavy roller for wicket preparation. This led to conditions that favoured spinners quite heavily.

England’s captain, Norman Yardley, won the toss and opted to bat first. However it was to be Valentine’s breakout match, the 20-year-old Valentine ended with first innings figures of 8/104. The magic did not stop; in England’s second innings, he bagged three more wickets, ending with match figures of 11/204.

The second Test at Lord’s, resulted in a famous victory. It was a victory that prompted a timeless piece of Caribbean music, ‘Victory Calypso’.

Michael Manley’s summation of that famous test match outlines the importance of that victory on and off the pitch ‘[…] over there in the bleachers, the people come from separate sovereign territories. Perhaps only when the cricket team is playing do they become West Indians and totally identified with the team and so with each other. Hence, the noise is a celebration of more than a commitment to a side. It reflects as well the longing of the West Indian for a time when the people back home can somehow come together to fashion a society from which they do not feel compelled to depart.’

The winning spree did not stop there. In the third match at Trent Bridge, the West Indies won by 10 wickets, with Worrell setting a record that would only be broken by Sir Vivian Richards at The Oval in 1977.

Worrell set the highest individual score by a West Indian in England, with a total of 261 runs. Manley said the knock was ‘complete mastery. There is no stroke that he did not play. At the same time, his cricketing intelligence was in control of everything that he did.’ Weekes also went on to score a fine century, 129 runs, and was only out by a good caught and bowled by Hollies, answering England’s first innings score of 223 with a resounding 558. A great effort from Johnson in the first innings with three wickets, Ramadhin and Valentine got eight wickets in their second innings, limiting England to 436. The West Indies were set a target of 101 runs, which Stollmeyer and Rae picked off with little or no fuss.

For the last match at The Oval, Valentine took 10 more wickets playing a major role as the West Indies went on to win the Test match by an innings and 56 runs.

Of the 38 matches the West Indies team played on the tour they only lost three. The series was and became more than just cricket; it was a means for the Caribbean diaspora to connect to their home soil, a celebration of Caribbean culture, of black excellence in England, dismantling the English establishment at their own game.

For its contemporaries, it was never simply about cricket, and less than a decade later, various politicians, writers, and thinkers from all parts of the Caribbean came together to form a federation. Although it might not have lasted long, for the people who were there and participated in its formation, its initially significance was clear.

What the West Indies means to Caribbean identity is a convoluted question, but I find it fitting to finish this piece with a Michael Manley quote: ‘The West Indies were unable to put a federation together and at times have difficulty in giving life and meaning to their regional economic institutions. At those times, the typical West Indian becomes tiresomely insular. But when the cricket team is playing, the whole area surges together into a great regional hubbub of excitement and involvement.’

Postscript:

This piece was a love letter to one of the two important topics in my life: Caribbean history and cricket. Not being either Caribbean or West Indian myself in any sense of the word, being born and raised in Brazil, I attempted to bring a different perspective on the rise of West indies cricket, not merely as a sports team, but as a ‘nation’. On the other hand, I did not want to tell Caribbean history from my own lense, but to let the Caribbean writers, politicians, writers, philosophers themselves tell this story.

I utilised many different sources from several different persons: Michael Manley was a huge inspiration, his book ‘History of West Indies Cricket’ is a brilliant piece of art, interpolating both the history of the team and the political events happening on the ground. His other book ‘Jamaica: Struggle in the Periphery’ is an excellent work facing the challenges of ‘Third World’ nations in an era of globalisation and international interdependence.

Other works which I used extensively were the biographies of Clyde Walcott ‘Statesman of West Indies cricket’ by Peter Mason, and Ivo Tennant’s ‘Frank Worrell: A Biography’, for the section on Rex Nettleford this wouldn’t be possible without the article by Marva A. Phillips ‘In Memory of a "Quality Black": Ralston Milton "Rex" Nettleford’, published in the journal ‘Caribbean Studies’.

On a personal note re: what West Indies cricket means to me, its been a part of my life since my early teens. My first interaction with it was watching the 4-Day Championship in 2019, the only team I watched was the Windward Islands for a personal liking of Grenada. Whilst considered a domestic bully, Devon Smith was a personal favourite of mine and his innings of 147 against Guyana in 2020 left an indelible mark.

Devon Smith may have introduced me to cricket but it was watching Jason Holder in 2019 at Kensington Oval that made me truly fall in love with cricket. Watching the match on my phone. Kemar Roach produced a brilliant spell of five wickets for 17 runs, limiting England to a measly 77 runs. But it was Holder’s 202 in the second innings that really got me hooked on the West Indies team. I still use that innings as a yardstick.

I was born in the countryside of Bahia, in a region nicknamed by the Portuguese colonisers as ‘The discovery coast’ for being the first place they invaded in South America. It’s a region devasted by poverty, having numerous cities in the top-10 homicide rates in the country, gang factions and rural working conditions are some of the worst in the nation. However one thing we do have is natural beauty, considered the most beautiful part of the country with lush green forests, the best beaches in the country and a famous tourist spot for Brazilians and South Americans in general.

For many of the people visiting a city like Porto Seguro, which is a couple miles away from where I was born, the poverty-stricken zones are completely hidden from the tourists and the only semblance of that is the number of muggings during the second biggest carnival in Bahia. Tourism brings a lot of revenue to the region, since it’s usually rich white urbanites wanting to escape the ‘traps’ of modern life, but as one can easily guess, corruption runs rampart and it’s the people and the system of public infrastructure and health care that suffers the most. I talk about this as I see a parallel with modern Caribbean society, and many of the struggles I have witnessed growing up.

My favourite batsmen to watch in regional cricket were and will still probably be Alick Athanaze and Kavem Hodge, I eagerly wait for the West Indies channel or the Windward Islands Facebook page to release interviews with both of them talking about their knocks and what they’re working on. Last year the dearest and most important person in my life passed away, I was devasted at the time but when I turned my computer on, I watched Kavem Hodge at Trent Bridge scoring his maiden test century. Hodge might never get picked for another West Indies game, even if he does he might not score another century, but for me that century during the saddest day of my life made me feel an internal joy which is hard to explain in words, that is what West Indies Cricket means to me.

Thank you to Luis Granada for part one of his article for the Caribbean Cricket Podcast substack.

The Caribbean Cricket Podcast is on Facebook and of course you can also find us on X and Instagram and all other social media platforms.

If you'd like to support the Caribbean Cricket Podcast you can become a patron for as little as £1/$1 a month - Here

You can buy the brand new Caribbean Cricket Podcast beanies now - please get in touch if you are interested in getting one.

You can also find out more about Caribbean Cricket Podcast at www.caribbeancricketpodcast.com