Stereotypes in the West Indies: Spinning Pitches (Part 1)

A debut article by Shastri Sookdeo looking at the myth behind spin in Trinidad and Guyana

Every country that plays cricket will have its own legends and stereotypes, especially in regions where the game has been played for decades. Cricket is often bound by tradition, and this can mean that ideas, when they take hold, can be next to impossible to shift. This is not a self-fulfilling prophecy and by no means results in teams refusing to adapt their styles to be successful in the modern game but instead may mean that the way teams are spoken about in the media and commentary box may occasional have more than a bit of stereotype about it.

Cricket is by no means unique in this, as football discussions can also seem to be stuck in a bygone era of expectations of defensive Italian football and beautiful attacking football from Brazil (though by now they’re both often showing up with robust midfields). The main difference, is that for many other sports, the commentary is an aside to the game. It’s easy to watch football or basketball on mute. Cricket, even a short form like T20, is quite difficult to watch without commentary. The dialogue between the commentators is necessary to fill the many pauses, and it is because of this importance that it’s necessary to look at the validity of commonly held stereotypes in the Caribbean.

While not everything can be backed up by data, many things can be. And though this article will likely never change minds in Facebook groups and rum shops, it may highlight that the feedback loops of expectations passing from commentators to fans, are possibly antiquated.

Spin in the West Indies

Spin is often an afterthought in the Caribbean, with the primary vision of the team outside the region being of aggressive fast bowlers. Locally, however, there is the perception that spin paradises exist in the Southern part of the region.

Trinidad and Guyana are expected to provide pitches where the ball turns. Certainly, when I was growing up, it was almost considered a mantra that playing spin well was integral to being successfully chosen to be part of any batting line-up in Trinidad. While there are locally held stereotypes as well, such as Central and South Trinidad being better for spinners, finding the data is difficult so the regional level will be looked at.

Seeing Permaul dismiss regional batsmen at Providence has been a regular sight

Since this stereotype is an old one, certainly predating T20 cricket and possibly ODI cricket as well, I’ve used the longest data set namely Test cricket which in my opinion, gives the added advantage of showing rewards for criteria that benefit spinners such as longer spells and worn pitches.

Main hypothesis: Guyana and Trinidad have pitches that are better for spin bowling.

To test this hypothesis, I’ll test multiple sub-clauses, the first being:

Matches played in Guyana and Trinidad should show better performances for spinners than other Caribbean pitches

This does not mean that the pitches in Guyana and Trinidad should have a larger percentage of wickets falling to spin overall or by a match-by-match basis. It could well be the case that fast bowlers dominate on these pitches as well, since West Indies have indeed had fast bowlers who can perform in almost all conditions in the more glorious bygone years.

It does not mean that the best match performances by West Indian spinners, such as Jack Noreiga’s 9/95 against India in 1971 could be considered as proof of the hypothesis because it was taken at the Queen’s Park Oval, any more than Lance Gibb’s 8/38 (from an astonishing 53 overs with an economy rate of 0.71) against India in 1962 can disprove the theory because he performed the feat at Bridgetown.

However, in comparison to figures in other parts of the region, any pitch can only be considered to be beneficial to spin if the wickets falling to spin show some kind of advantage.

While the figures for Trinidad and Guyana may not look like overseas spin paradises in the sub-continent, it is important to benchmark the context as regional and not global, which is why similar statistics abroad are not looked at.

However, I split visiting spinners and local spinners into two views, to take into account any difficulty travelling players may have in adjusting to the conditions (though this assumes all players from all other regions adapt at the same speed, which may be flawed due to differences in preparation and structures in their respective regions).

The figures:

The three grounds being considered are the three with test status: Queen’s Park Oval, Bourda and Providence Stadium.

Bowlers considered at the top 50 in terms of total wickets taken for the selection criteria, so the top 50 visiting spinners, top 50 home pace bowlers etc. I have not included Sir Garfield Sobers, mainly because it is difficult to tell which wickets were taken when he was bowling fast and when he bowled spin (clearly a player who would manage in all conditions).

The data considers all matches played from 1930 (the year of West Indies’ first Test match).

There are only 42 players in the history of West Indies cricket who have taken wickets in the Caribbean in Test cricket while bowling spin in Trinidad and Guyana. Though I knew spin was underutilized in the region, the fact in 93 matches few spinners have had opportunities or success is still surprising.

Figure 1

So, at first there doesn’t seem to be a significant advantage for spinners at the Test level, in Guyana and Trinidad. Away spinners average 33.45 runs per wicket in the Caribbean in general. While they are indeed more economical for wickets taken at Guyana and Trinidad, the difference of only 0.59 runs per wicket is functionally not very significant. If the figures for the Caribbean are taken with Trinidad and Guyana excluded, then the average goes up to 34, meaning that visiting spinners cost 1.14 runs more when they have wickets outside of Southern Caribbean. While not a massive difference, it does give light credence to the initial assumption.

Local spinners are more expensive than their foreign counterparts, both in Trinidad and Guyana as well as across the region. With the average being just 0.72 runs less per wicket on the supposed “spin friendly” pitches, the advantage is not yet apparent. If we compare figures for the Caribbean without Guyana and Trinidad versus with, there appears a gap of 1.19 runs per wicket with the Trinidad and Guyanese wickets taken by spin proving to be cheaper at 36.86 compared to 38.05. While this is again not a large variance, the fact that the home and away figures are correlated seems promising about the stereotype holding up.

Tangentially, away spinners average less than the global average (37.57) no matter where in the region they bowl. West Indian spinners only average less than the global average in Guyana and TT

Figure 2

The average is not the only measure of a bowler, and indeed, the saying is that Trinidad and Guyana are better for spin bowlers. So, this doesn’t necessarily mean they bowled economically. Perhaps this could mean they were more threatening, which can be looked at, in proxy, by bowling strike rate (amount of balls taken per wicket).

It becomes harder to find a difference with the away bowlers. With a wicket every 83.6 deliveries, Trinidad and Guyana do indeed have the least amount of deliveries needed for a spinner to get a wicket. However, overall the strike rate is 83.8 and excluding Trinidad and Guyana only takes the strike rate to 84. But, the trend still holds for the hypothesis that it’s easier, even incrementally, for spinners in Trinidad and Guyana.

However, the home team’s figures complicate matters. West Indian spin bowlers take the most deliveries to get wickets in Trinidad and Guyana, needing 8 deliveries more than they do in other grounds in the Caribbean.

While this doesn’t guarantee that spin isn’t favoured in the three most southernly Test venues in the Caribbean, the figures don’t back it up.

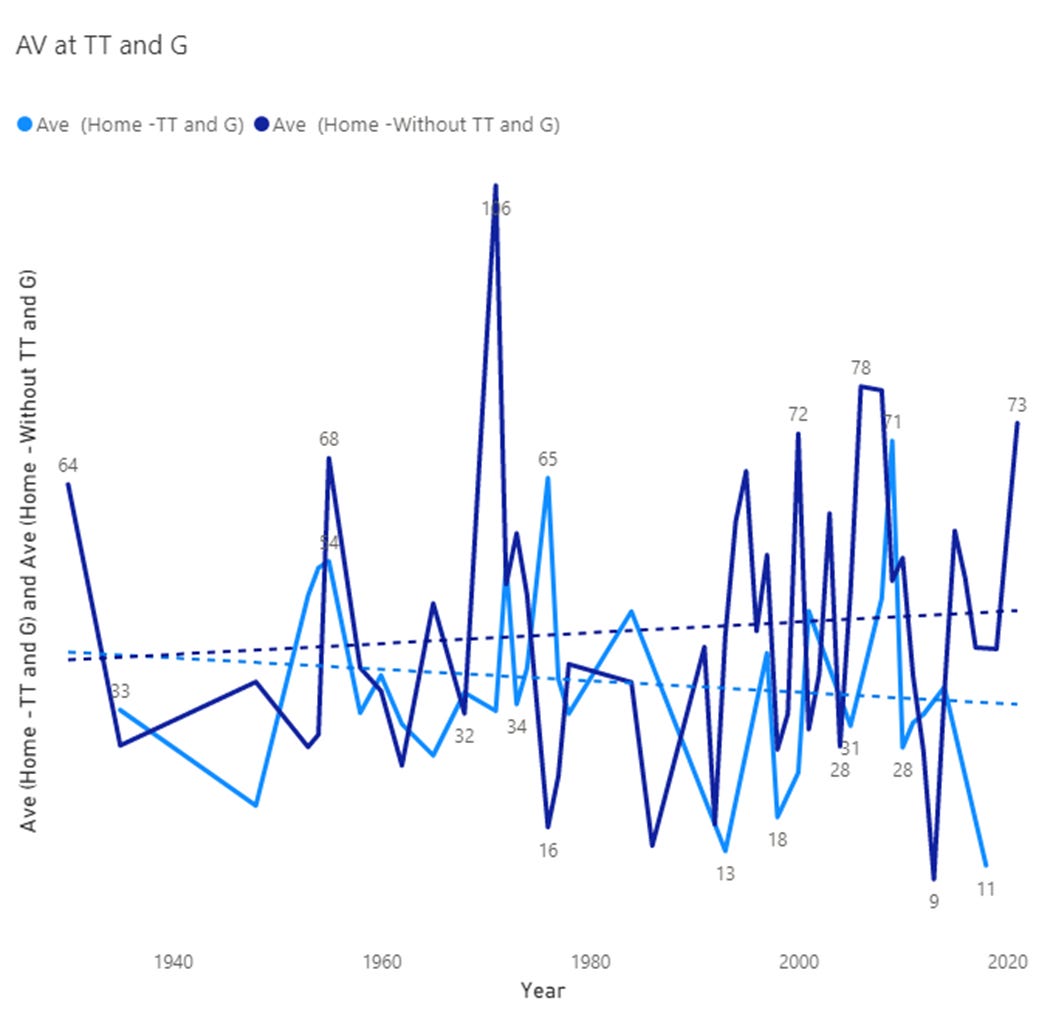

Figure 3 & 4

Could it be possible that these grounds used to be spin-friendly but now are no longer so, and so may be a case of outdated ideas still holding sway?

I’ve only included years where 2 or more wickets were taken since there are years where 1 wicket taken gives averages in excess of 200, which distorts the year-by-year look quite a lot.

Both on the strike rate and average measures, the dark blue line is almost always above the light blue one. This does seem to suggest that Guyana and Trinidad, most of the time, are somewhat better for spin bowlers but the fact that there are not large gaps and erratic shape of the curve means that it isn’t clear cut at all.

On the point of averages, the trend lines are divergent, which itself means there are clear differences between bowling spin successfully in the South Caribbean as opposed to the rest of the region. This trend figure, more than anything else, is where an argument for playing spinners in Trinidad and Guyana can be made. Spinners’ wickets are more expensive in the rest of the Caribbean since 1940 and the gap continues to widen, with wickets falling to spin becoming cheaper every year up to the last matches played (2018 in Trinidad against Sri Lanka and 2011 in Providence against Pakistan, with Bourda no longer holding Test status after the 2005 Test against South Africa).

The strike rate doesn’t provide as clear of a divergence, since strike rates across the region for spin bowlers are decreasing. However, the strike rates for spin bowlers in the Southern Caribbean are decreasing faster than in the rest of the region, as seen by the widening gap between both lines.

Conclusion

So far there is no immediate proof that the pitches in the Southern Caribbean are better suited to spin. While the evidence does show very small advantages are gained on the hypothesized spinning pitches, there is not enough of a gap in the performance statistics to really say there is an impact . Since the difference in averages for spinners outside Trinidad and Guyana are only around 1 run more. If spinners take all wickets the advantage would be 10 runs saved.

With the strike rate 8 balls more for spinners to take wickets, any savings in runs would be compensated by an extra 80 balls in the field.

There is not yet a way to measure the effect on the batting from staying a further 13 overs in the heat, but it would be unlikely to be positive. Hence, it seems any advantages for spin, based solely on strike rates and averages, cannot be confirmed.

Strangely enough, recent trends are proving some truth in the statement with averages of spin bowlers going down in the Southern Caribbean compared to the rest of the region. Strike rates are falling across the region in general, which suggests pitches overall are slowing down, but the rate is falling faster in the South Caribbean. However, for a stereotype to be established it could be expected that past statistics resemble the current ones, which is not the case.

However, perhaps there are more ways to see this. Certainly fans are basing this assumption on the eye test and not statistics and they have not limited themselves to the proclamation that the spinners bowl better but that batters also play spin better.

Part two will look at whether batters from Trinidad and Guyana show greater ability against spin bowling than their Caribbean counterparts, which would pass the eye test up to fairly recent times with Lara, Hooper and Chanderpaul. It will also be worth a look at whether batters who average highly and do not get dismissed often against spin, find themselves with lower averages or more frequent dismissals in Trinidad and Guyana.

___________________________________

As ever if you would like to have content published in the newsletter by all means feel free to drop us an email.

Leave a comment or reply via email with your response to Shastri’s piece. Your interaction is what helps grow the community and we appreciate every response.

To keep up to date with latest content on the Caribbean Cricket Podcast do head to our You Tube page where we have daily videos for you to watch covering the big news stories in the Caribbean as well our podcast.

If you would like to discuss any sponsorship/collaboration opportunities or find out more about the podcast - visit our website - www.caribbeancricketpodcast.com

Great analysis here. Amazing how our eyes can see what we expect them to see. The priming effects of the stereotypes about each ground and inherited wisdom around selection is probably related issue to investigate