Sunil Narine - The King of T20 spin bowling

Has any other bowler revolutionized the art of T20 spin as much as Sunil Narine? Karthikeya Manchala analyses the craft of the Trini spin king.

“That’s the first wicket of the night for the king from Trinidad” - exclaimed Dinesh Karthik, former KKR captain, after Narine dismissed Jos Buttler in The Hundred.

Trinidad, often called the spiritual home of T20, has produced some of the pioneers of the format. Kieron Pollard pushed the barriers of T20 finishing, Dwayne Bravo was one of the first specialist death bowlers, Samuel Badree started a quick wrist spin revolution and most recently Nicholas Pooran has shown us the model spin hitter. Then there’s Sunil Narine.

Narine is...the pioneer of mystery spin. Oh wait, he’s also cricket’s front page pinch hitter. Actually, all that should just be a footnote, there is so much more.

Around 2014, the ICC began clamping down on suspect actions, throwing a spanner in the careers of Ajantha Mendis, Saeed Ajmal, Shane Shillingford and more recently, Akila Dananjaya.

The training and effort required to remodel an action one has used from grassroots level, but also the mental fortitude required to overcome a habit, is unimaginable - never mind the stress of knowing you are probably one mishap away from your career ending. Yet, Narine is still here and winning matches for his T20 franchises.

In the never-ending conversation about the legality of his action, his overall legacy and his choice to skip World Cups for the West Indies, we often ignore one basic question - what is Sunil Narine now - i.e. what has actually changed?

What is a suspect action and when was Narine called for one?

The ICC describes a suspect bowling action as follows: “where a player is throwing rather than bowling the ball where the player's elbow extends by an amount of more than 15 degrees”. During the 2014 Champions League T20, Narine’s “faster ball” which we will soon see was his stock ball was reported for a suspect action. In 2015, Narine’s off break was suspended by the IPL.

It was the final jerk in Narine’s action, when he was releasing the ball at a faster pace, that caused him to get into hot water. Think of it like a spring releasing - Narine bends his arm to an extent and then jerks it to apply pace on the ball.

Watch the release below:

The ball is like a grenade and it is coming fast

It is one thing to turn the ball both ways like Narine does, but it is a completely different proposition when it is coming at pace. The batter has much less time to look for cues and pick which way the ball is turning. It also gives the batter fewer seconds to pick the length and move forward or back - one of the key requirements to play spin well.

Quick note: From here on, we take data from the IPL because (a) it is available to us and (b) it is where Narine’s action actually keeps getting called, but more because of (a).

Before 2014, Narine was the fastest off spinner in the IPL - heck, it is not even close. He was the 4th fastest spinner after Axar Patel, Ravindra Jadeja and Daniel Vettori - all left arm spinners and the first two only turned the ball one way.

Post 2014, Narine’s average speed dropped by roughly 3 kph. Still fairly fast because he bowls a flat trajectory, but now he is not even in the top 5 fastest off spinners or top 10 fastest spinners. Sure, not all turn the ball both ways, but it was a clear sign that the spin bowling landscape changed. Narine started a trend and the world followed it, while Narine himself fell behind.

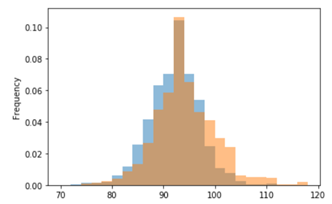

Below is a graph showing Narine’s speed distributions 2014 and earlier (orange) and post 2014 (blue). The blue curve is not only slightly shifted to the left, but the right-tail is very significant. You can see the number of “quicker balls” Narine bowled drastically reduced.

Staying behind the sweet spot

T20 spin bowling is nothing close to Test match spin bowling. The goal in T20 is largely to restrict runs whereas long formats necessitate wicket taking. The strategy is simple - bowl the ball behind the swinging arc, i.e. do not let the batsman get into a power position. Power positions and slogs are usually off the front foot, so it is ideal to bowl back of length.

But in reality it is not that simple because multi-format spinners in the early days of T20 struggled to adapt to the change in requirements.

That said the sweet spot is 5-6 metres. It is in the back half of a good length ball - not full enough to get into a power position and not short enough to go back.

The length by length record in the last four years is shown below -- it is clear that the 5-6 metre length is best to contain runs. While bowling further up produces more wickets, the runs tradeoff is high. The best “containing strategy” is to aim for the sweet spot with your margin for error being behind the sweet spot rather than in front.

Pre-2014, Narine bowled 29% of his balls in the sweet spot, above the global average of 27%. Good, but not spectacular. But wait for it, he bowled 71% of his balls in the sweet spot or behind it, well above the global average of 50%. It is ground-breaking, a simple shift in strategy but incredibly effective.

Narine’s sweet spot and behind the sweet spot numbers are the same post 2014. But the global averages increased to 29% and 57%. It is one thing that Narine has not changed in his bowling and it is why it is still hard to score boundaries off him.

Another fantastic aspect of Narine’s bowling is his control of length. Pre-2014 Narine bowled only 6% bad balls (overpitched or drag down) and that improved to 4% post-suspension -- in both cases, top 5 in the league. That slight improvement was necessary because Narine’s bad balls began to become slightly more expensive post-suspension, likely because batters did not necessarily have the mindset to block out every ball.

The box of tricks

Narine has two significant variations - the off break and a knuckleball. He bowls inswingers, carrom balls, and whatnot, but not as frequently. The off break that he flicks out using his fingers turns towards the right and the knuckle ball which he lodges between his knuckles and shoots out turns towards the left. Before his suspension, he also had a doosra which turned towards the left.

Since it was Narine’s off break that was banned, it was his record against left-hand batters (LHB) that was more substantially affected.

While Narine’s record against both LHB and RHB weakened, it is against LHBs that he is struggling more against now. The explanation is fairly simple - the primary ball against LHBs is the off break which Narine couldn’t (a) bowl as much and (b) turn as much. That being said, it is still against conventional wisdom for an off spinner to perform worse against LHBs than RHBs -- something teams should take note of.

This becomes evident when we take a look at the direction in which Narine’s balls deviate after pitching for both RHBs and LHBs pre and post 2014.

Deviation in metres for RHB 2. Deviation in metres for LHB

Blue = pre 2014, Orange = post 2014

The graphs above show how much Narine’s balls deviate after pitching. Positive deviations mean the line at the stumps is further to the right than the line at pitching. Negative deviations mean the line at the stumps is further to the left than the line at pitching.

The deviations to LHB are largely positive because of the angle Narine usually bowls from - over the wicket to LHBs (more on that later). The distributions pre-2014 and post-2014 are massively different -- since he cannot bowl much of the off break, Narine relies more on the knuckleball and is unable to take the ball away from the LHB as much to cause trouble. The turn he gets from his off break is much less too.

Against RHBs, the distributions are largely similar. The only notable observation is that his knuckleball used to turn more before suspension, but that might just be due to the nature of pitches he played on or because the knuckle ball turns less than the doosra.

How much Narine can turn the ball now is less in his control, it is a tough skill to improve at this stage of his career. But one of the reasons why Narine is a genius is because he finds ways to stay relevant in the game. One of his latest additions to his arsenal is hiding the ball behind his back.

By hiding the ball until the last motion of release, the batter cannot pick the ball from the hand. Since Narine bowls a roughly even split of in-spin and away-spin these days, it is almost a coin toss which way it will turn. Hiding the ball is not a new tactic, but Narine has made it repeatable and hides in until very late, making it so effective.

Are we nearing the endgame?

Is the the present version of Narine the last iteration we will see? He was called for a suspect action again in the 2020 IPL but made a quick comeback. Since then, the most noticeable change in his bowling was his switch to round the wicket against LHBs.

Before 2021, Narine almost never bowled round the wicket to LHBs. Going over the wicket to the opposite handed batter is incredibly rare but it is what made Narine unique as the apparent deviation from a straight trajectory is higher. There may be two reasons why Narine has made the switch.

The first reason is why any bowler may want to switch to round the wicket - to bring lbw into play more often. The ball is less likely to pitch outside leg stump and the angle attacks the pads more. But that does not answer why Narine made this switch despite going over the wicket all his career.

It could just be action mechanics. Try picking up a ball (if you don’t have one in front of you, try performing the action), lift your arm straight and release it at a straight angle. Not too hard. Now try pitching it to your right, still facing straight. Not like lifting a mountain but slightly harder. Since Narine’s action is very straight on, angling the ball away from LHBs is slightly unnatural. That slight difference could be causing the flex in Narine’s arm, forcing him to go round the wicket like every other off spinner.

Narine the pinch hitter

There are so many pieces out there that do more justice to Narine, the pinch hitter, but this story would not be complete without a brief look at least. Narine is a natural batter - one can see that with the conventional strokes he plays. But it was only during his break that Narine really started to take it seriously by training hard - he knew he needed to add value in different ways to continue being an in-demand T20 player. The result: IPL 2018 MVP.

The value of Narine’s wicket in his usual position is at best +1 run. By using him up the order, even if he makes just 17 off 10, Narine is adding a value of about +5 runs (an intuitive approximation) given typical top order batters start slowly. If he gets out early, it is just a +1 run value you are losing out on. Narine’s role is to attach zero value to his wicket and impressively he does it all the time.

Narine’s real USP, though, is against spin bowling. Since 2017, Narine has struck at 12.46 RPO against spin in the IPL. The next best - Nicholas Pooran - is not even close at 9.81. By pairing up Narine with a pace hitter, either at the top or in the middle overs, teams are forced to either bite the bullet or use up an extra over of premium pace at Narine. The upside is massive and there is virtually no downside unless he has a horror day where he can neither hit or get out.

Recently, Narine has massively struggled against hard length and high pace bowling, reducing his effectiveness as a batter. Yet, recently in the Hundred he seemed to have worked on that and played cameos facing the bowling of high pace seamers. We won’t know if this is a real improvement until we see more of it, but if it is, should we really be surprised?

So back to the question - what is Narine?

Narine’s previous success is partly because of his illegal action, we must admit. But as we’ve seen, it is his genius and methods that made him an outlier. Narine is now a decent T20 bowler and a valuable T20 package, but his methods have changed T20 spin bowling - a pioneer like his fellow Trinidadians.

So...Dinesh Karthik is right, Narine is the King of Trinidad and the King of T20 bowling. A King who never accepted mediocrity as an option, no matter how much he was pushed. Yes, he is now dethroned by Rashid Khan. But once you earn the title of King, it always remains with you.

___________________________________

As ever if you would like to have content published in the newsletter by all means feel free to drop us an email.

Leave a comment or reply via email with your response to Kartikheya’s piece. Your interaction is what helps grow the community and we appreciate every response.

If you missed it we dropped Episode 47 of the podcast, Shimron Hetmyer joined us to discuss his career past, present and future. This was a raw and very open conversation.

If you would like to discuss any sponsorship/collaboration opportunities or find out more about the podcast - visit our website - www.caribbeancricketpodcast.com