One of the most respected books about any sport is Beyond a Boundary by C. L. R. James, published in 1963.

James was a Marxist historian who for decades campaigned for independence for those countries in the Caribbean under British rule. Today, he is commemorated almost as much for Beyond a Boundary as his work in other spheres. For anyone writing about the history of West Indies cricket, it is an invaluable book.

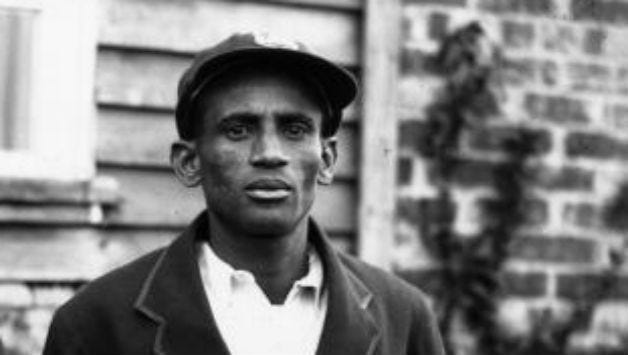

The most remarkable chapter is about Wilton St Hill, who played three Tests for the West Indies between 1928 and 1930 with little success. Alongside Learie Constantine and George Headley, he forms part of James' narrative which links sport, West Indian excellence and politics. Were it not for Beyond a Boundary, St Hill would have been long forgotten; instead he lives on, particularly in more academic works about cricket. Less well-remembered are his two brothers, Edwin and Cecil. They feature briefly in Beyond a Boundary, although Wilton is clearly the central character.

The three brothers played together only once in first-class cricket — when Trinidad routed the defending champions Barbados in the final of the Intercolonial Tournament in February 1929 — but regularly appeared in the same team in local Trinidadian cricket. They were from the Woodbrook area of Port-of-Spain and part of a lower-middle-class family. Wilton was born in 1893 and Edwin in 1904. We do not have a date of birth for Cecil, who was probably the youngest.

There is no question that Wilton was the most famous, respected and revered of the three. For C. L. R. James, he was one of the most important figures in Trinidadian and West Indian cricket. In Beyond a Boundary, he demonstrates how much Wilton meant to the people of Trinidad. He describes how he had a large and devoted following, who closely watched his achievements and revelled in his many successes.

In a world dominated by the white Europeans who administered many regions of the Caribbean on behalf of the oppressive British Empire, black men and women had little opportunity for advancement in the face of racism, discrimination and blatant favouritism towards the white minority. One of the few places presenting any opportunities was the cricket field.

James explains how black Trinidadians awaited St Hill going to England to score runs at Lord's and show what the West Indian people could achieve given the chance: "The unquestioned glory of St Hill’s batting conveyed the sensation that here was one of us, performing in excelsis in a sphere where competition was open. It was a demonstration that atoned for a pervading humiliation, and nourished pride and hope … Wilton St Hill was our boy."

Everyone had expected him to be chosen for the tour of England by a West Indies team in 1923. They hoped he would establish his reputation throughout the world; that he would be signed to play professional cricket for an English county or in league cricket — the path Learie Constantine so famously followed in the late 1920s. However, Wilton was overlooked in 1923.

Wilton eventually overcame his disappointment and through a string of excellent innings in the mid-1920s, including a century against a strong touring team from England in 1926, proved himself the best batsman in the West Indies. Therefore, when a team was chosen to travel to England in 1928 for a tour which would include the West Indies' first Test matches, he was an obvious selection. But in England, Wilton was, as James conceded, "a horrible, a disastrous, an incredible failure". He could not — or perhaps would not — temper his aggressive style to take account of the alien conditions. Too eager to hit the ball to the boundary, he continually flashed at balls outside his off-stump, and averaged a touch under eleven in first-class games. He played in the first two Tests, but achieved little.

However, not all of Wilton's problems in 1928 arose on the field. James openly admitted that Wilton was a difficult man. In fact, he comes alive far more as a man than as a cricketer in James' writing: "Fires burned within St Hill and you could always see the glow … [George] John I understood. St Hill I could never quite make out. His eyes used to blaze when he was discussing a point with you, but even within his clipped sentences there were intervals when he seemed to be thinking of things far removed." Part of the reason he was omitted in 1923 was that other players were more easy-going; only when his weight of runs made the case unarguable in 1928 was he selected.

Some of this may have emerged behind the scenes during the unhappy tour. The West Indies captain Karl Nunes horribly mismanaged his team, ostracising anyone who challenged him. An anonymous but well-informed report in a Trinidad newspaper claimed that Wilton was one of those cast aside by Nunes after an incident in an early game when he dropped a catch and kicked the ball away. It is questionable that such an event occurred, but undisputable that Wilton played less and less as the tour progressed, until he completely vanished from the team.

Perhaps his disappearance from the tour was through an unreported injury or illness. More likely, he was dropped as punishment for standing up to Nunes or for some incident lost to history. James is silent on the subject in Beyond a Boundary — although he must have read the article which had a considerable impact in England and the Caribbean.

Wilton returned home a shadow of his former self. The visit of another England team in 1930 relit some of the old fire, and he scored a century for Trinidad. This earned him a last Test appearance in which he scored 33 and 30 — hardly a failure — but that was his final first-class game.

The remaining years of Wilton's life are a blank: outside of the pages of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack and Beyond a Boundary, he is a mystery. No sources even identify his middle name, other than it started with "H". Nor is there any record of his death, but he was certainly dead by early 1957 when Constantine wrote about him in Wisden. James finished his chapter in 1963: "He saw the ball as early as anyone. He played it as late as anyone. His spirit was untameable, perhaps too much so. There we must leave it."

Wilton's brother Cecil is an even bigger enigma. Cricket sources like ESPNcricinfo list him under his nickname Cyl, give no birthdate for him, nor record his death. All that is known is that he was a left-arm fast bowler, and we only know this through a brief mention in Beyond a Boundary. James details how the fast bowler George John "for some reason or other" hated him, and that Cyl "was the type to say exactly what he thought of John, preferably in John's hearing." Like Wilton, Cecil may have been a fiery character. He played just the one first-class match, alongside his brothers, but did not bowl as he had suffered an injury. Nothing more is known of him.

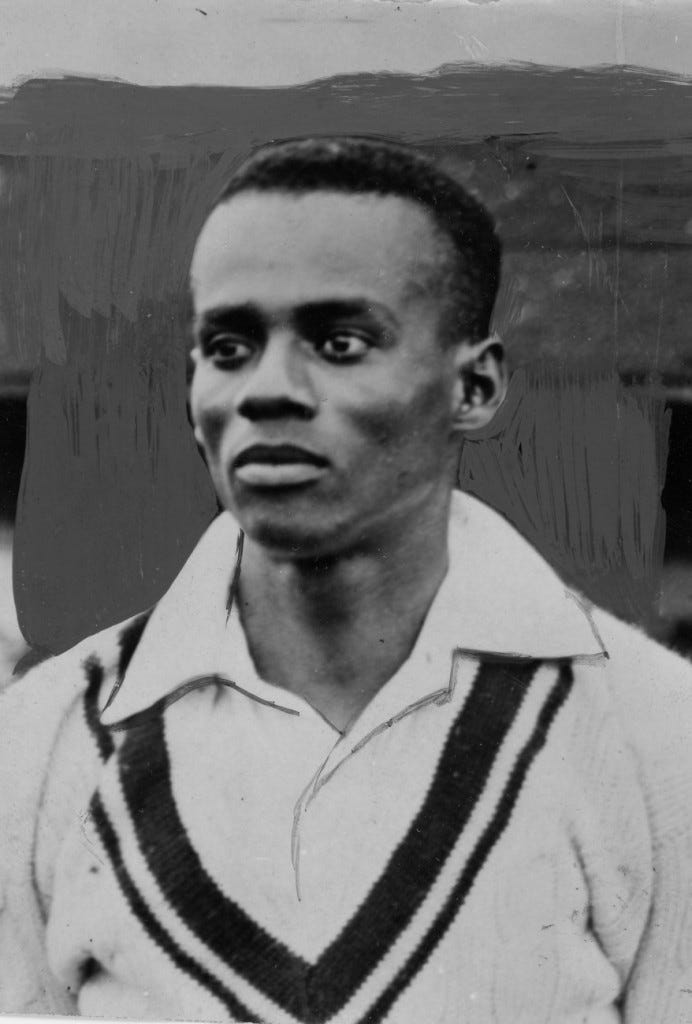

The third brother Edwin never attracted the same attention nor excitement as Wilton and seems to have been a more placid figure than Cecil. An all-rounder, he was an accurate bowler and an entertaining batsman, but was not a cricketer to set pulses racing. As a result, he has been somewhat neglected by the cricket world. But in many ways his story is the most interesting of the three St Hills.

Edwin started more slowly than Wilton, gradually establishing his place in the Trinidad team in the mid-1920s and progressing to the Test team in time for the visit of England in 1930. In that series, he was noted for his accuracy but little else. However, it was enough for Lowerhouse, a club in the world-famous Lancashire League, to sign him as their professional for the 1931 season based on little more than a recommendation from Constantine, then playing for Nelson, Lowerhouse's rivals in the league. Around the same time, Edwin married Iris Orvington in Trinidad. Days after the wedding, he set off for Australia with his West Indies team-mates for a tour there.

In Australia, Edwin had few opportunities as the pitches did not suit his brand of medium pace and he did not play any of the Test matches. Following the tour, he never played first-class cricket again; the remainder of his career was at club level. He travelled directly to England with Constantine and George Francis, the other two West Indies players involved in league cricket, in time for the 1931 season.

Edwin was a success at Lowerhouse in that first summer and signed a contract for a further two years. After spending the winter at home in Trinidad — where he was reunited with Iris, having been away for almost a year — he returned to Burnley for the 1932 season. This time, Iris went with him and the couple attracted a great deal of attention from the local press.

While playing for Lowerhouse, Edwin spent time with Constantine, who lived nearby, and the pair remained close afterwards. One curiosity is that Edwin must have known C. L. R. James when the latter was living with Constantine in 1933. Yet James makes little mention of Edwin in Beyond a Boundary, and although league cricket and the factors which drove Constantine to seek a life away from Trinidad are a huge theme within his book, James does not even note in passing that Edwin made a life in England.

Although Edwin continued to be relatively successful at Lowerhouse, he did not quite reach the heights of his first season, nor those of some other professionals in the league. Consequently, in 1934 he moved to Slaithwaite in the Huddersfield League and enjoyed an extremely successful season, attracting large crowds as the most famous player to represent the club. However, Slaithwaite made a loss through his record-breaking contract and did not renew it.

Edwin now began a nomadic existence, playing for several clubs in Yorkshire and proving both popular and successful wherever he went. First he spent two years at East Bierley in the Bradford League, then one year — curtailed by a serious illness which resulted in a prolonged stay in hospital — at Lascelles Hall in the Huddersfield League. The following season he joined Spen Victoria in the Bradford League and, after struggling to shake off the effects of his illness in his first season, proved one of the best bowlers in the competition during 1939. On the outbreak of the Second World War, Edwin joined the army and was involved in the evacuation of Dunkirk. Military duties restricted his cricket in 1940, although he still managed to play once for Spen Victoria and several games in the Border League while still in the army.

Discharged for unknown reasons in 1941, Edwin returned to Spen Victoria for two seasons before moving to the Central Lancashire League and playing for Crompton in 1943 and 1944. And in 1945 he returned to Slaithwaite and took an eye-watering number of wickets. Throughout this time he worked as a machinist in Bradford, but played regular wartime charity matches for various teams of West Indies cricketers.

After Edwin played for Walsden in the Central Lancashire League in 1946, he largely disappeared from the records. He certainly had spells at Kearsley in the Bolton League and Vickerstown in the Cumbria League, although by then he was considerably past his best. But he remained associated with West Indies cricket, even playing alongside members of the triumphant 1950 team such as Frank Worrell, Everton Weekes, Clyde Walcott and Sonny Ramadhin in some friendly matches in the early 1950s. With his career as a professional cricketer over, he worked as a clerk at the Ministry of Fuel and never appears to have returned to Trinidad apart from a brief visit with his wife in the mid-1930s.

The evidence suggests that Edwin's marriage was not a happy one. The cause may have been his affair with a Burnley girl in 1933 when he was the professional at Lowerhouse. She gave birth to a daughter shortly afterwards; Edwin was not named on the birth certificate but was almost certainly her father. Although Iris initially remained with her husband — she moved to Slaithwaite with him — they were living apart by the 1950s, and may have separated in the late 1930s.

Edwin, living alone in a boarding house in Manchester at the time, died of a stroke in 1957, aged 53. He was buried in Manchester's Southern Cemetery, but his grave remains unmarked in 2021. Not far away in the same cemetery is the grave of his estranged wife, also unmarked; Iris died at the age of 81 in Manchester in 1987. It seems a great shame that the graves, so far from home, of a pioneering cricketer and his wife lie without any memorial. But at least, unlike his brothers, the story of Edwin St Hill can be told in some detail.

________________

If you are unaware we have recently started a Patreon page where we have exclusive content for those who wish to subscribe.

The aim is to keep this Substack newsletter free and open to all but our Patreon will feature some brand new audio-visual and written content going forward as we look to expand our media offering. Please go and take a look here

As ever you can find all our podcasts wherever you listen to yours - search Caribbean Cricket Podcast. Alternatively you can find all episodes here - Podbean

This week we will be recording episode 36 with Trinidadian Rishi Persad - the current frontman on Channel Four for the India vs England Test series.

Absolutely fantastic piece, thanks for that. I have been fascinated about the St Hill's and George John since reading Beyond A Boundary, but info is very hard to come by. Wilton is written about in reasonable length in Harry Pearson's book "Connie" given that both St Hill and Constantine broke through around the same time when playing for Shannon.