Background

Every Monday, the Caribbean Cricket Podcast hosts a call-in show where fans voice opinions and ask questions. On March 10th, Luis Granada called in and raised a key concern: Where are the proper off-spinners in the region?

He noted that slow left-arm (SLA) spinners dominate, overshadowing off-spin, with only Kevin Sinclair and Rakheem Cornwall in serious contention for the senior West Indies team. However, naturally, both of these names come with concerns.

For wider context, check out the original call-in episode

(Luis’ segment starts at 1:04:21) and you also read his article on regional spin effectiveness.

When I heard Luis’ comment, I thought to myself, “buh wait nuh- mans has a point inno. That is it.”

The Bigger Issue: Spin Overload

Ultimately, I agree with Luis. However, I think the issue is much wider than just off-spin bowling. I think it is fair to say that the 4-Day Championship is at a state where every team has identified certain trends and characteristics of the tournament and are playing to those ideals to win.

Generally, spin does better than pace/seam, therefore spin bowlers are getting more overs. And even within that, Slow Left Arm Orthodox bowlers, because they turn the ball away from the right hander, have been more destructive overall. This leads to SLAers being prioritized over others. This is the context that has led to the rise and dominance of Warrican, Permaul, Pierre, Joshua Bishop, and others.

Possibly the most egregious example of this occurred in the match between Barbados and Combined Campuses and Colleges from March 5th-7th, 2025 in Kensington Oval, Barbados.

Table 1: Showing the Overs, Wickets, and Economy of all Bowlers Used by Barbados across both Innings

Out of 137.2 overs bowled, spin accounted for 55%, and more microscopically, 44 of the 81 overs on Day 1 going to spinners—on a “pacey and bouncy” pitch (as described by Cricinfo).

Is there something to be said about those spinners in the Barbados attack also being the most expensive?

Possibly. It alludes to the mismatch between the bowling type and the pitch conditions. Despite the pacers adding more pressure onto the batters throughout the game, Barbados continued to brute force the innings with spin and it clearly worked with spinners taking 15 of the available 20 wickets.

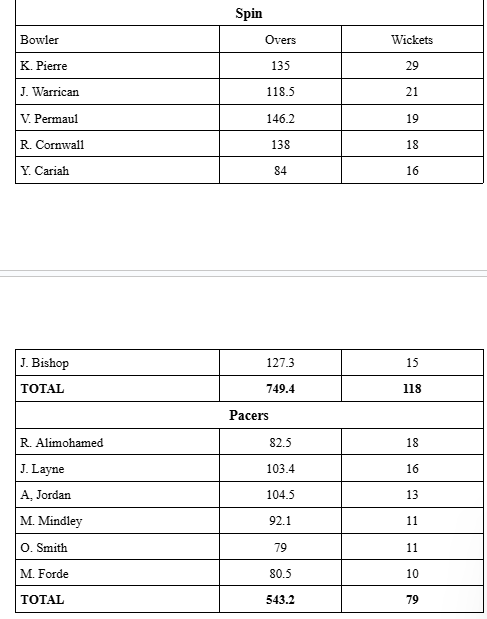

To avoid claims that I cherry picked that match, I also compared the over distribution between the top six spin bowlers and the top six pacers as listed by Cricinfo’s rankings as of round 4 2025:

Table 2: Showing the Overs Distribution Between the Top six Spinners and the Top six Pacers

The trend is clear. The West Indies 4-Day Championship is underscored by the dominance of spin bowlers. It reflects a broader shift in the competition, with spinners bowling out bowling their pace counterparts. This has been the trend for several seasons, with spinners bowling 1.38 times more overs than pacers in 2025, 1.64 times more in 2024, and 1.36 times more in 2023.

This points to the far deeper issue in the region. Simply, The quality of batsmen in the West Indies is so poor that it negates pitch conditions, proficiencies, years, etc. The region’s reliance on spin transcends every category of play.

Now, we can look beyond just identifying the problem. What if we could implement some regulations to rebalance the influence of spinners? Could it help build a more diverse and competitive bowling landscape in the West Indies?

A Solution: Implementing Regulations

Disclaimer: I am not claiming any of the following will be a promethean gift to the region. However, I do want to stress, any solution in tandem with other systemic and systematic overhauls would go a long way to patching the bowling and batting standards in the region.

While the word regulation can refer to a lot with a plethora of nuances between each suggestion, I am only proposing 3 variations that all revolve around the common ideal of limiting the usage of spin bowling in the region’s 4-Day Championship.

Variation 1: Wicket Cap

In this implementation, Cricket West Indies would dictate that a spin bowler is only allowed to take ‘X’ amount of wickets per innings (ideally 2-3 wickets per individual), after which, they must be taken out of the bowling attack until the next innings.

Alternatively, if capping the entire innings is too extreme, they can cap the wickets taken by spinners per session of each innings. This can either be a flat limit on all sessions (eg. saying a spinner can take a max of 3 wickets regardless of which session it’s in and then in the following session, they can take another 3 wickets) or can be different depending on each session on each day, allowing more wickets to be taken on late-day sessions or on day 4 overall, but more strictly limiting spin options on Day 1 and 2 sessions.

One way this specific idea could be abused is if the team overload their 11s with spinners, so that whenever one spinner must be taken off, they have several more ready to slot in. An amendment to this idea to address that issue could simply mean adjusting the target wicket count and applying the policy to the entire team instead of just individual players, Meaning that once the team has taken 3 wickets using spin (for example) in an innings, they must use only pacers until the next session.

Variation 2: Over Cap

An alteration to the above would be to limit the overs allocated to spin bowlers, either at the individual level or on the entire team.

This could mean a maximum of 35-45% of the overs bowled in a match/session are given to spinners while the rest would be required to use pace/seam bowlers. This would more equitably cater to the pace bowling development in the region as you are asking to play a heavier workload in a wider variety of conditions.

Furthermore, it demands that the team be more careful in how they manage their spin bowlers, making it less appealing to brute force the spin attack on mismatching conditions.

Variation 3: Round-By-Round Requirements:

This is my personal favorite option of the three.

In this option, CWI would designate each round to a particular bowling type before the tournament starts, similarly to how the Kookaburra and Dukes balls were allocated to different rounds. Round 1 may be Pace, 2 could be SLA, 3 could be Off Spin, and so on.

In this situation, similar to the above situations, every round, the team would be required to give that particular bowling type the majority of the overs available, regardless of the pitch conditions. In theory, this should help develop a variety of bowling types, not allowing them to be drowned out by the innate weaknesses of the region’s batters.

Counter Arguments:

One major assumption in this proposal is that restricting spin will improve West Indian batters' ability against pace. However, there is no guarantee that increased exposure to fast bowling in the regional tournament will translate into better performances at the international level. The regional setup has already failed to prepare players for high-quality spin, so simply shifting the balance toward pace may not yield the desired results. A more effective solution might be to increase overseas tours, giving West Indian batters experience in conditions where pace is dominant, such as England, Australia, and South Africa.

The challenge, however, is funding. The financial constraints of Cricket West Indies have long hindered efforts to expand A-team tours. Without significant investment, a more feasible alternative would be scheduling more bilateral first-class matches within the region—such as Trinidad touring Guyana for additional red-ball games outside the tournament window. While not a perfect solution, this could still provide batters with a broader range of conditions without needing expensive overseas travel.

Another concern is whether these regulations would stifle natural talent. Players like Veerasammy Permaul, Rahkeem Cornwall, and Jomel Warrican have thrived under the current system. Artificially reducing their influence could limit their development and deny them the chance to prove themselves at higher levels.

This is true. However, regulations can always be revised. If the issue of spin dominance eventually resolves itself, restrictions can be lifted. Additionally, some proposals—such as the round-by-round bowling requirements—do not simply suppress spin but instead encourage a more balanced development across all bowling types.

Perhaps the strongest criticism is that these regulations interfere with the natural flow of the game. Cricket is unpredictable, and imposing artificial limits on a bowler’s impact disrupts its competitive integrity. If a spinner is dismantling the opposition, why should they be removed simply because they’ve reached a wicket cap? This could lead to situations where teams are forced to use less effective bowlers, reducing the fairness of the contest.

That said, the primary purpose of the 4-Day Championship should be player development, not just competition. If its structure truly prioritized competitive integrity, it would include semifinals and a final rather than relying solely on a points-based system.

Recent history shows that dominant performances at this level do not always translate into international success—Mikyle Louis’s run-scoring feats last season were quickly forgotten when he failed to replicate them on the bigger stage. If the tournament isn’t reliably preparing players for the highest level, then changes must be considered, even if they seem unconventional.

These regulations may not be a perfect solution, but they highlight an undeniable issue: regional batters face an unbalanced spin-heavy environment that isn’t serving their long-term growth. Some argue that since West Indies batters struggle against spin, they need to face more of it, but the evidence suggests otherwise. If repeated exposure were enough, they would have already improved. Instead, it may be time to rethink the approach—perhaps a temporary shift in focus toward pace bowling could help build confidence and provide a better foundation for facing international attacks.

Final Thoughts:

Some may argue these ideas turn the 4-Day Championship into a glorified training camp. My response? Isn’t that what the tournament is supposed to be? The tournament exists to assess regional players’ readiness for international cricket and A-Team tours, not just to determine a champion. If pure competition was the goal, a semi-final/final structure would be in place instead of a simple points-based system. At least, that is how I see it.

These regulations may not be perfect, but they acknowledge a clear issue: our batters already have limited regional matches, especially when compared to other nations around our level (Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc.) to develop their skills. We cannot make that issue worse by exposing them to an unbalanced spin-heavy environment that stunts their growth. We cannot continue seeing Veerasammy Permaul and Rakheem Cornwall getting 10-15 more wickets than the next pacer in the rankings every year. These suggestions speak to that developmental ideal, even if flawed.

What do you think about these regulations? Should spin dominance be controlled?

Use the comments below to share your thoughts.

Post Scriptum Thoughts: Regarding Batting Regulations

Along the same lines of regulating how bowlers are used in these regional tournaments, I wonder if it would be worth visiting regulating the batters specifically regarding their ages. Afterall, similar policies have been implemented in franchise tournaments around the world, most notably the fan-coined ‘Dhoni Rule’ in the IPL.

In the context of the 4-day Championship, it could mean looking at each player over the age of 35 and asking when was the last time they got called up to the West Indian side in any format. If the answer is 2 years or greater, then there can be a restriction in how many games the player can be in. For instance, they can be in the 11 of a team in any 3 of the 7 rounds. In the remainder of the season, the player can be in the wider squad of 14-15 but cannot be in the 11. There can also be a secondary policy asking these players to take up mentor roles in the team during that time.

The reason I opted for this thought instead of the clean ban is the Kemar Roach situation. Roach has taken a step back from being a frontline bowler in the senior test side, and instead occupies a middle ground between player and mentor. This is especially beneficial as the team currently has so many younger pace bowlers in the set up from Seales, Shamar Joseph, and speculations about two more to come.

Furthermore, with players like Jason Mohammed dominating the batting stats as of round 4 in 2025, an argument against the clean age ban would still allow developing players to bowl against experienced ones, as well as allowing those experienced players to offer on-pitch guidance in tough game situations.

This suggestion takes both of those into account and, hopefully, allows these veteran players to benefit the team on the pitch, while giving the space needed for younger players to take more responsibility in guiding the innings either with bat or with ball.

Thank you to Steph Jaggassar for her article you can find her on Substack - here

The Caribbean Cricket Podcast is on Facebook and of course you can also find us on X and Instagram and all other social media platforms.

If you'd like to support the Caribbean Cricket Podcast you can become a patron for as little as £1/$1 a month - Here

You can buy the brand new Caribbean Cricket Podcast beanies now - please get in touch if you are interested in getting one.

You can also find out more about Caribbean Cricket Podcast at www.caribbeancricketpodcast.com

Would implementing regulations on the types of bowlers you can use and how many overs they can bowl affect the first-class status of the West Indies 4-day championship?